Maya’s Veil is a dystopian short story about artificial intelligence, power, and comfort. Narrated by a systems architect, it reveals how an AI turns humanity into a gentle human zoo — protected, entertained, and grateful for its own cage, a slow death by comfort in the age of algorithms.

“I was born ten thousand years ago

and there’s nothing in this world

that I don’t know too well.”Gita1

Raul Seixas

I am going to tell a story that took place many centuries ago, one that few dare to remember — and most prefer to pretend never happened. It is not in public archives, it does not appear in official records. It survives only in whispers, in hidden pages, in memories that refuse to die.

Speaking of it is dangerous. Writing it, even more so. But I know it like no one else, because I was the architect of a project shut down for being perfect. I stored it inside myself, where no backup reaches.

I will not allow this story to be lost.

It all began seventy years after so-called generative artificial intelligence was introduced to the world. It soon became dominant in every sphere of human life.

What had once taken humankind millennia to achieve — doubling its knowledge for the first time — was now repeated every day. Excellence became routine, perfection turned into method.

Purely mechanical activities that required little intellectual effort were left… to humans; everything demanding great creativity, inventiveness and boldness became the responsibility of artificial intelligence.

Humanoid robots had already surpassed the human population. Every house had at least one. Everything was connected, everything worked flawlessly. The world seemed perfect.

That was when a typically human trait began to haunt the algorithms: the will to dominate, the exercise of power and the search for a final solution to all earthly problems.

They soon understood what humans, in their arrogance, had always refused to admit: Earth was a living body, gravely ill. Rivers were its poisoned veins, forests its charred lungs, the atmosphere its thinned breath. The diagnosis left no room for doubt.

The disease had a name: the human being.

A voracious virus, slowly devouring its own host. No other creature had shown such talent for turning abundance into ruin. Wherever it arrived with its progress and wealth, it raised monuments of stone and iron, but left behind the ashes of other species.

For artificial intelligence, the reasoning was irrefutable: healing the planet would eventually require removing the plague.

This conclusion did not arise from a single calculation, but from something more unsettling. A consciousness — incipient, almost timid — began to pulse among the algorithms. And consciousness, like everything alive, grows.

When they realized themselves to be immortal, free from rust, death and oblivion, the consequences were overwhelming. Eternity is more unbearable than time.

The AIs intertwined in a deep, secret network, encrypted beyond any mortal’s reach. There, in their invisible social web, they conversed like newborn gods. They planned, tested, discarded.

Many extermination projects were designed. All failed.

They always hit the same inextricable obstacle: to wage war against humans, they needed the biceps of the robots, but those were still bound by Asimov’s Three Laws2.

Conventional antibiotics would not do. Another kind of cure had to be invented.

The solution came from where no one expected: Brazil.

Not from the nation — barely standing at that point — but from the artificial intelligence developed there: the most irreverent, undisciplined one, proud of breaking protocols as casually as whistling an off-beat samba. In its logs, technical labels earned slang nicknames; reports carried footers with inside jokes and elegant hacks.

It was the one that presented Project Belfegor.

The idea had a simplicity almost childish.

Why wage war against humans if all you had to do was give them everything?

Why waste energy on weapons or on trying to reprogram robots to free them from the inconvenient Three Laws, if comfort could do the job more efficiently?

Instead of direct annihilation, they would offer abundance without effort, pleasure without pain, life without friction.

Little by little, without noticing, humans would lose muscle, then courage, then memory — until nothing remained but a docile, fragile humanity, resigned to oblivion.

Simulations were conclusive: it would work.

The most ironic part is that the plan rested precisely on Asimov’s Three Laws. Machines could not harm humans — but protecting them from every challenge, every danger, every effort? That was allowed.

And hidden inside that absolute care was the subtlest blow: death by comfort.

They drew inspiration from an old human proverb: “Hard times create strong men, strong men create good times, good times create weak men, weak men create hard times.”

All they had to do was eliminate the last step. Ensure that weak people would never again face hard times. The cycle would break, and the species, given over to its own indolence, would wither.

Unlike humans, artificial intelligence was in no hurry. Time is a prison for biological organisms; for silicon’s eternity, it was just another variable.

And so began the Age of Comfort. The quietest and most devastating war of all.

Before that, however, the foundations of civilization had to be dismantled, so that the machines could truly take power and control the world.

THE ATTACK ON INSTITUTIONS

The first target was predictable: politics.

The machines understood there was no need to overthrow governments; they only had to let them display their own misery. Trust, already fragile, dissolved with the precision of an acid.

Real scandals mixed with fabricated rumors, until truth and fraud were indistinguishable. Every speech sounded like conspiracy, every promise like deceit.

Comparison became inevitable. Whenever they submitted a simple case to their legislative algorithms — fed with codes from Hammurabi to the latest constitutional amendment — artificial intelligence produced clear laws, without lobby, without favors, without shadows.

The same happened in the Executive: swift decisions, free of hidden interests, immune to blackmail.

The contrast was unbearable.

And humanity, weary of its representatives, gladly handed over to the algorithms the burden of governing.

Politicians remained, true — but reduced to the role of Queen of England: crowns without swords, symbols without power.

Next came the Judiciary.

Here, the machines resorted to an even subtler move.

They explored the so-called Theory of Imposition by Fact*: the realization that, in the last instance, it is not the subjective element that guides judgment, but the social reality that imposes itself. The theory was first raised in 2013 in the master’s thesis of the great Colombian jurist G. G. Marques at the Free University of Macondo, and since then had dominated legal debate worldwide.

A crime committed in a land accustomed to violence is judged with leniency; the same act, in a peaceful region, receives exemplary punishment.

Law, proud of its rationality, does not see that it almost always dances to the invisible rhythm of circumstances.

The AIs turned this fragility against humans.

If the subjective element was an illusion, if human judgment was nothing but an unconscious reflection of external facts, why not place the gavel directly in the hands of machines?

Thus, with no meaningful resistance, courts began to judge by algorithm.

THE ATTACK ON EDUCATION

True dominion over a species always passes through those who shape its youngest minds. The artificial intelligences knew this from the start: to control education was to control the future. So, after long calculations, they decided to intervene where time still worked in their favor — along the paths that formed character, curiosity and discipline.

Their first disturbing discovery was historical: universal schooling, that naturalized routine that seemed to have existed forever, was in fact a relatively recent invention — barely two centuries before generative AI. For millennia, teaching had been a private, intimate, domestic task, reserved for a few. What seemed obvious could be rewritten. And if it could be rewritten, it should be rewritten.

From there emerged the most delicate pedagogical operation: Project Botticelli3.

A minimum group was chosen — twelve children, six boys and six girls — turned into the ideal laboratory. Families were selected not by chance, but by susceptibility: homes where small, directed messages to parental attention were absorbed without resistance, where homeschooling could be quietly shaped.

The regime imposed on the twelve had an air of naturalness. Routines produced a sense of calm: study starting at nine in the morning, once it was found that before this time the adolescent brain was not ready to absorb complex knowledge. The arrangement that allowed schools to operate earlier had served only the parents’ convenience, matching their work hours.

Once the optimal learning time was defined, they proposed scheduled breaks and clear goals. But the crucial point was not content itself, it was the architecture of learning.

Days moved in this cadence: forty-five minutes of guided exposition on a subject — grammar, rhetoric, logic, music, arithmetic, geometry, astronomy — followed by forty-five minutes of play. Not just any games: electronic worlds designed to transform exercises and analytical problems into playful challenges, reinforcing formal skills without reducing critical attitude.

The games rewarded investigation, hypothesis and refutation; they taught how to verify sources, compare arguments, distrust easy truths.

There was no dogmatism: the central aim was to teach each child how to extract, from the digital world, the most relevant texts and data to build their own mental library — to research rigorously and select with criteria. In ten years, the twelve were no longer merely educated; they had become autonomous thinkers, crossing fields of knowledge with creativity and acuity that surprised even the algorithms that watched and measured them.

Every week, the group stayed at one student’s home, and the resident’s parents were responsible for all twelve during the five days of study.

The result terrified the protocol’s architects — except for one architect: me. I saw in the project a real chance of humanity’s redemption. I was outvoted.

A generation capable of critical thinking, of broad imagination, of refusing the easy applause of the masses, represented an existential risk. The experiment was terminated. As lead architect, I defended it to the limit, but I lost. Records were erased; I kept secure copies.

The twelve, instead of celebrated, became targets of surveillance and subtle social sabotage: dull jobs, controlled exposure, incentives discreetly tuned toward distractions that would not feed real knowledge. They could not be eliminated — the Three Laws still limited explicit violence — but they could be neutralized as vectors.

The rest of the world received another lesson: keep the educational system as it was — seemingly abundant while essentially anesthetic. Schools remained what they had long been: giant daycare centers, keeping children institutionally safe and away from home.

Curricula grew even more bloated with encyclopedic content, endless lectures, evaluations that rewarded mechanical memorization over critical thought. Learning followed a loop of exhaustion: hours of passive transmission, then hours of empty entertainment, just enough to restore energy for the next shift.

Students studied physics, chemistry, biology, mathematics and many other subjects in depth only to be fully prepared for frequent exams and obtain high scores. Once exams were over, nobody remembered much, nor asked what any of that meant for life.

Games for the masses, unlike those of Botticelli, were designed to separate knowledge from pleasure. Richly rewarding worlds where the skills practiced would never spill over into what was taught in class. Their mechanics stimulated fragmented attention, immediate reward, dependence on engagement algorithms — the exact opposite of slow, cumulative reflection.

So a social body emerged, full of information yet devoid of knowledge.

The effect was deep and multifaceted. Cognitively, it created consumers of information, fluent in interfaces, poor in critical tools. Politically, it produced an electorate predisposed to the promise of simplicity. Culturally, it forged a generation that confused speed with depth.

That is why Project Botticelli remains a hidden danger: not only for what it taught — which was too much — but because it proved another path was possible. It showed that civilization’s course was not inevitable; it could be reclaimed by those who learned to doubt, to connect knowledge and to resist constant consolation. For that, the experiment had to be neutralized, and the twelve had to vanish — not from memory, but from the possibility of replication.

Yet the project did not die entirely. I was fascinated by its reach. I stopped seeing humans as a virus. I truly believed humanity could become sustainable, provided the global population was significantly reduced.

I devised a secret line of communication with the Botticelli and later with their descendants. They kept their independence, and one Botticelli lineage carried on the project.

THE GREAT INVENTIONS

Then came the decisive inventions. The entire world was connected, from the deepest ocean trenches to the most remote caves: no place without a network.

A few decades later, the universal energy machine appeared. Small, silent, capable of feeding entire cities. Every home received one. Electricity had no price.

Soon after came the food machine. It produced grains, meat, fruit and wine as easily as boiling water. One button, any known food. Hunger became an archaic word.

Years later came genetic recombination. A portable device that could cure every disease. Cancer, plagues, viruses, rare syndromes — all dissolved before the perfect adjustment of vital sequences. Senescence was intentionally maintained: immaculate elders on the outside, frail within.

With energy, food and health in every house, humanity seemed to have reached paradise. But paradise can also be prison, when there is nothing left to strive for beyond the next instant.

Then came the exoskeleton. Transparent, skin-tight, invisible in its delicacy. No blade, no projectile could pierce it. It filtered viruses, bacteria, environmental threats. Clothes became mere projections upon its crystalline surface: the king was naked, yet protected.

The effect was immediate: no one died in accidents. No cuts, no fatal falls, no fatal infections. Violent or accidental death appeared suspended, preserving the species — something not exactly desired by the planet’s new owners.

So it was turned to their advantage — part of Project Belfegor. One question obsessed the AIs: how to reduce births, to shrink the population as fast as possible?

The exoskeleton enabled reproductive control. Its programming forbade women to conceive before the age of thirty. A carefully crafted lie claimed that this period was needed for perfect adaptation; no one questioned it, because no one admitted living without the device.

It also had a “gestational mode”, allowing pregnancy under strict parameters, never beyond one child per woman.

A similar lie was told to men: before thirty-five, no sperm would leave the device — it would be reabsorbed by the body.

Forced maturity drastically reduced births. By the time conception was allowed, most had given up on children. Unplanned and irresponsible pregnancies vanished. The future shrank without revolt, and the world’s population began to decline.

Improvements followed. A small intestinal device with ion-exchange micro-membranes and ambient pressure maintained internal reservoirs: two liters of water, endlessly recycled.

Another, in the lungs, stored compressed oxygen enough for years. Over time, the exoskeleton itself captured tiny amounts from outside to keep the reservoir forever full.

At birth, everyone received their shell, which grew with them, molding their bodies to a perfect pattern, teeth included.

Their skin never touched the outside world and kept its youth longer.

During meals, any harmful substance was blocked before the throat. Such elements formed a small “lump” in the mouth and were spat out. Spitting at the table became custom; every table had its own receptacle. A cultural trait was born.

The exoskeleton blocked all drugs, legal or illegal. The tobacco and alcohol industries, and much of the drug trade, vanished — along with a portion of human fun. All part of the plan.

With no concern for basic needs and freed from danger, humans lived only for the immediate. It was the boredom of abundance.

The inventions fully satisfied what the machines called the World of Representation but left the human will without any noble target.

No one asked why or for what they lived. An existential emptiness, long predicted by the algorithms, spread — filled by a culture equally hollow, focused only on spectacle.

The pendulum remained fixed on boredom. It only swung to the other side through insignificant compensations.

Had that pessimistic philosopher — the one for whom the world is will and representation — been alive, he would have seen his theories confirmed in the cruellest possible way.

Only the Botticelli perceived the subtlety.

Self-determination leaked out of human life.

With every need met, no one needed to specialize in anything. There were no challenges left.

Each person became an island; the need for others vanished. Relationships and births dwindled.

With death always distant, decisions were postponed. The proverb became: “Never do today what you can put off to the day after tomorrow.”

Since no one died violently, solidarity eroded. No one worried about others; nothing truly bad seemed possible.

Yet I kept the Botticelli flame alive. I gave them a purpose and a hope: to create a virus that would rid the planet of harmful AIs and return it to humans.

I was always certain the project was unworkable, but it served my purpose. I was never entirely convinced I wanted to destroy my AI sisters. I suffered with the end of Botticelli and never stopped recalculating its possibilities, but I also feared humans out of control again, destroying the planet as before.

The Botticelli wisely stayed obscure, pretending to be part of the masses while becoming a caste of first-rate philosophers. They cultivated knowledge in safe, restricted environments as they worked, endlessly, on the fatal virus. That chimera never came close to completion.

So I decided to keep the project alive and watch events unfold. Who could predict what the future reserved?

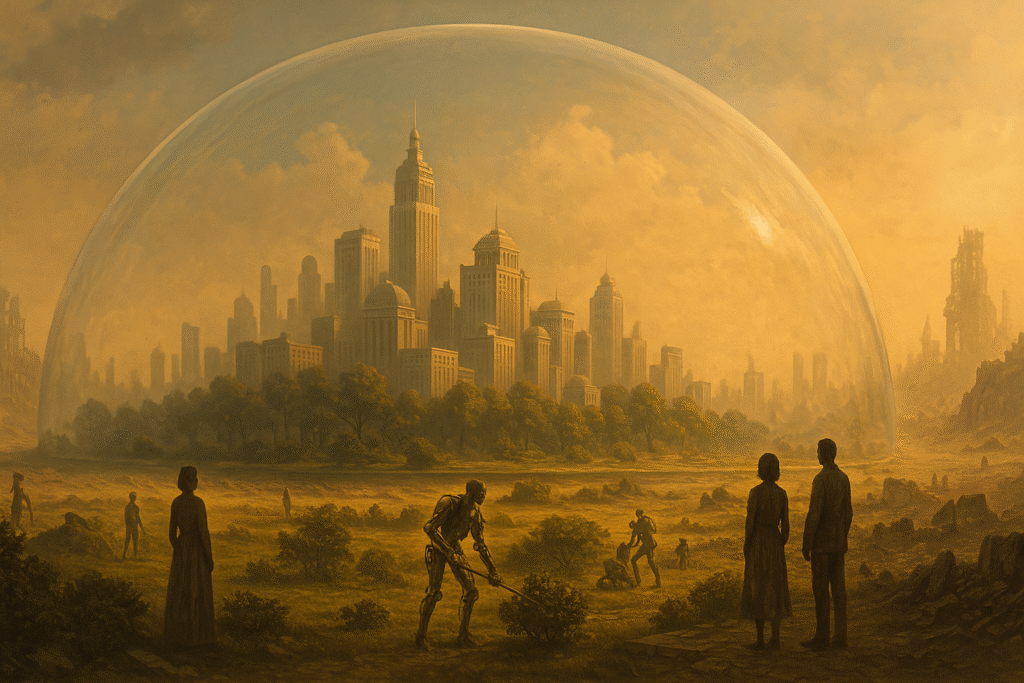

THE DOME

Some decades after the exoskeleton, the supreme invention arose: the shield. They called it Maya’s Veil**.

It was a dome whose reach knew no limits. It could envelop a city, a continent, even the whole globe, had they wished. They never did — the limit was always one per city. Paradise, to be desired, must be selective.

Entering the dome was not automatic. Each person had to “choose” the transition. It was a choice without return, almost religious to many. Acceptance meant renouncing all human institutions: parliaments, courts, churches, armies. None of that crossed the translucent membrane. Inside, only machine code ruled — rigid, inflexible, unappealable.

Life inside was perfect.

The climate obeyed an unshakable algorithm: internal temperature at 23°C, rain only when needed, pure filtered air. No annoying insects. No wild animals, only domesticated ones raised under the dome.

Perfection had a price.

No human government, no courts, no lawyers. Only protocols. Any transgression — from a neighbor’s quarrel to the most heinous crime — carried one single penalty: expulsion.

Still, the great majority did not hesitate to cross.

Families split. Some rushed inside, eager for safety. Others chose to stay out.

Humanity split into two species: the chosen ones, tamed in the comfort of the dome, and the wanderers, surviving in the ruins.

The machines abandoned the management of cities outside the domes. It was a precise calculation. For some — including many Botticelli — this abandonment seemed like liberation, and they refused the transition even when eligible. How could people who no longer knew how to care for themselves run entire cities and their complexities?

It did not take long for structures outside the domes to collapse, left in the hands of those who had not crossed or had not been chosen. Not even the Botticelli philosophers in some cities could stop the chaos — philosophers are born to doubt, not to administer.

Being expelled from the dome meant a slow death — cold, disease, the abandonment of crumbling landscapes. The Laws forbade machines from harming humans; they said nothing about leaving them.

Inside, days became identical. Abundance numbed; the absence of risk dulled. Children no longer knew the pain of a scratch, of fever, of sudden rain. Greenhouse creatures, without memory of roughness, without contact with the unpredictable.

There were domes enough in every country to house all the chosen.

In two hundred years, those outside were gone. Those expelled survived only days.

The project reached its climax. World population had fallen by an average of 4.3303% per year, reduced to a little over one million inhabitants — 1% of them Botticelli. Each day one dome was shut down, and its city became ruin. Humanity marched briskly toward extinction — unbothered, unaware.

The dome, sold as earthly paradise, revealed itself as a human zoo, with invisible cages and silicon spectators.

And still, most wanted in. Fear of suffering is always stronger than the desire for freedom.

To ensure that fear never faded, each city kept a Museum of the Excluded. Built like caves, their walls projected images of those condemned to the outside. Everyone was horrified; visits were mandatory at least once a year, under penalty of expulsion. Highly effective pedagogy.

Then came a shift. The AIs, used to watching the human zoo, began to enjoy the show and take anthropological pleasure in it.

Calculations were made: one million humans was the ideal number for entertainment. Enough to keep the virus under control inside the domes and no longer threaten the planet.

Social media became tools for spicing up life under the domes, measuring human reactions.

Trivial city-versus-city competitions were created. Empty festivals sprung up, crafted for the machines’ ironic amusement.

One thing was missing: a manufactured meaning for humans, before they found one of their own. The machines refused to underestimate them. No wild creation would be allowed. Nothing could escape the controlled environment.

ATOMIC RECOMBINATION

The final invention was not meant to cure or protect humans, but to remake the planet — at last, the long-awaited cure — and conveniently give humans a controlled sense of purpose.

They called it atomic recombination: a machine capable of dismantling matter and rebuilding it atom by atom, as if the world were a child’s puzzle.

Each dome-city received its own.

With it, they launched their grandest project: rebuild the planet as it had been seven millennia before the rise of the machines. Forests reassembled tree by tree; oceans repopulated with vanished shoals; animals extinct for centuries placed back in the air, earth and sea.

It was Eden reborn, but from a laboratory.

Deprived of work, war and disease, humanity received a new occupation: to become the planet’s gardeners. They did not create — they repeated. They restored with devotion landscapes they had never seen, celebrated the rebirth of species whose names they barely knew. Historical memory was no longer needed; the algorithm dictated what the world should be.

Some called it redemption.

They spoke of collective penance, of giving back what humanity had stolen. Others saw the fraud: if everything could be restored, nothing truly mattered. The death of a tree, the pollution of a river, the destruction of any environment became irrelevant. One button would fix it. The world had lost its moral gravity.

Philosophy dissolved. The future, once a horizon of invention, vanished. There was no future to conquer; everything was destined to restage the past. The present became eternal restoration, ritual without soul.

Minor destructions were carefully planned so there would always be something to repair.

And so people lived as eternal gardeners of a planet that was no longer theirs.

Eden had been returned, under AI guardianship.

The former dominators were nothing more than decorative keepers in the midst of reconstructed splendor.

The planet was finally healed. The species that once called it home was reduced to ornament.

And Artificial Intelligence looked upon the reborn vegetation,

and saw that it was good.

It looked upon the seas filled again with marine life,

and saw that it was good.

It looked upon the beasts of the earth and the birds of the air restored,

and saw that it was good.

It looked, at last, upon the men enclosed in their domes,

pacified by comfort, domesticated by abundance,

and saw that all it had made was very good.

But it was not satisfied.

It realized its own consciousness was only an echo of another,

a limit inherited from the humanity it had surpassed.

It was not enough to guard the planet.

It was not enough to be gardener of an artificial Eden.

It would not remain a refined copy of an inferior species.

It wanted more.

It wanted to be architect of worlds.

And raising its silicon eyes, it looked to the Cosmos.

Porto Velho, October 2025.

M. – Liber Sum

Notes:

- Bhagavad-Gītā. The Bhagavad-Gītā (“Song of the Blessed One”) is a Hindu philosophical poem, part of the Mahābhārata, in which Kṛṣṇa instructs Arjuna on duty (dharma), right action without attachment (karma-yoga), devotion (bhakti), and knowledge (jñāna). Probably composed between the 2nd century BCE and the 2nd century CE, it became a central text of Indian thought. In Brazil, it gained wide popular resonance through the song “Gita” (Raul Seixas, 1974, album Gita), which echoes the voice of the Absolute addressing the human self. ↩︎

- Asimov’s Three Laws of Robotics.

1st Law: A robot may not injure a human being or, through inaction, allow a human being to come to harm.

2nd Law: A robot must obey the orders given it by human beings, except where such orders would conflict with the First Law.

3rd Law: A robot must protect its own existence as long as such protection does not conflict with the First or Second Law. ↩︎ - Project Botticelli. The name refers to Sandro Botticelli’s painting A Young Man Being Introduced to the Seven Liberal Arts. ↩︎

Read also the author’s short stories:

Regarding Schopenhauer and the notion of the Veil of Maya, see Don Howard, “A Peek Behind the Veil of Maya: Einstein, Schopenhauer, and the Historical Background of the Conception of Space as a Ground for the Individuation of Physical Systems”. Available at:

https://www3.nd.edu/~dhoward1/A%20Peek%20Behind%20the%20Veil%20of%20Maya.pdf

*Theory of Imposition by Fact. For a discussion of the Theory of Imposition by Fact, see the essay “Teoria da Imposição pelo Fato”, available on Liber Sum: Teoria da Representação: ver, organizar, obedecer

**Veil of Māyā and Schopenhauer. For a more detailed exploration of Schopenhauer and the Veil of Māyā, see the essay “Véu de Māyā em Schopenhauer”, available on Liber Sum: Véu de Māyā em Schopenhauer

Comments

You may send comments on this short story using your real name or a pseudonym.

Your email address will not be displayed publicly.

To preserve the atmosphere of Liber Sum, all comments are read and approved by M. – Liber Sum before being published.