“Life’s but a walking shadow, a poor player

That struts and frets his hour upon the stage

And then is heard no more.”

— William Shakespeare, Macbeth (V, v)

Aesthetic Decline: Art, Applause, and the Loss of Measure

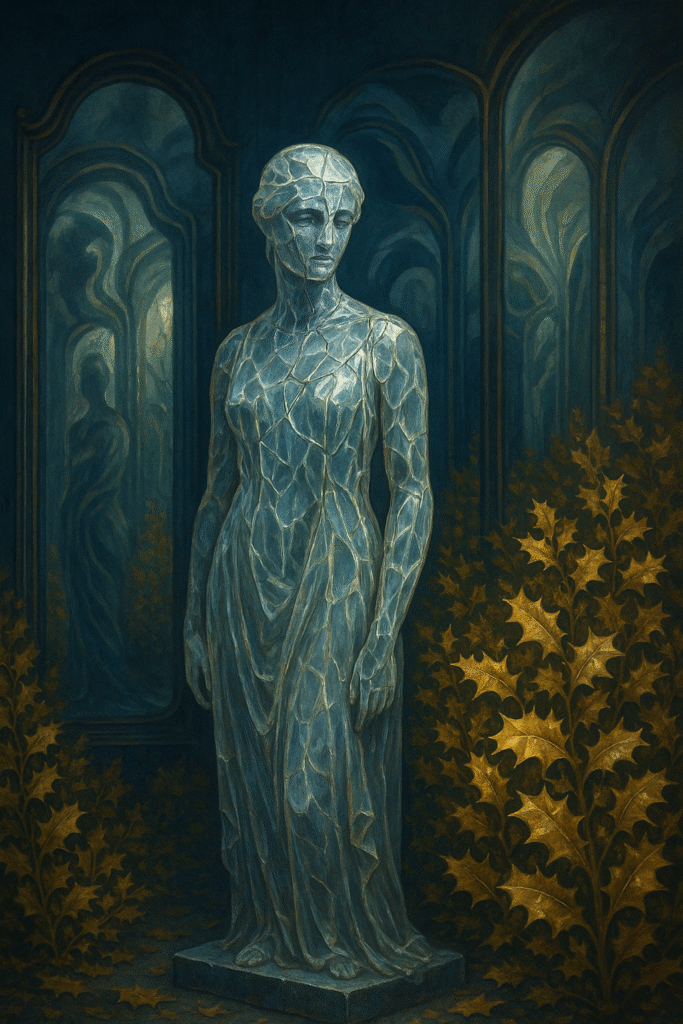

In a city that figures on no map — whose celestial coordinates are α = 1h 13m, δ = +14° 17′ 01″ — surrounded by holly groves no one remembers planting, stands the Academy of Mirrors. It is neither museum nor theatre, but a house of many rooms where the more you look, the less you see.

There, years ago, an annual prize was created, of variable prestige and constant gossip: the Oracle of Astonishment, known worldwide as Uncle Herrick, awarded to personalities of the artistic world. It takes the form of a crystal statuette.

Alongside it, a parallel prize arose, with a name as enigmatic as it was solemn: the Reed in the Wind. The trophy is a golden reed shaken by the wind, upon a crystal pedestal. No one asked whether the wind blew from the direction of art or fashion; and no one seemed to notice that, in this case, the gold was leaf-thin, made to bend and glitter only while the gust lasted.

In that house of reflections, I understood early that aesthetic decline is not a sudden collapse, but a delicacy gradually traded for noise.

I worked for some time as caretaker of surfaces in that Academy. I learned to polish mirrors. The first secret is paradoxical: excessive polishing gives too much truth; it is wise to let truth fail a little, so the image flatters and does not denounce aesthetic decay. The second secret is moral: nothing reflects as fiercely as a public in a hurry to see itself as virtuous.

In that city lived an old family whose coat of arms bore a musical scale and the royal cubit of Karnak: Nobile, the father, whom intimates called Good Taste; Kalía, the mother, known as Aesthetics; and their son, Lucio Speculo.

Lucio Speculo grew up charming, almost gentle. He was generous at the bar, polite with technicians hauling cables, and possessed a rare talent for giving the common crowd the comfort of proximity to the salons. Alone, however, he spoke of himself as a sad chosen one: born too late for epics, too early for ruins. At first, it sounded like mere literature.

One day, the Academy announced the theme for the Oracle of Astonishment: “Transgressions that free us from invented chains.” The call applauded, with feigned sobriety, those who mocked the shackles of the age — provided it was done with the appearance of courage. Transgression, there, had a protocol.

Then Lucio Speculo presented his project: a film of restless camera, poor lighting and casual speech, in which Art — capitalized out of habit, treated in lowercase — appeared hand in hand with the Prostitution of Art. No shells or harpoons; only exposure. Sex as punctuation, drugs as sharp accent marks. Beauty violated for no apparent reason but violation itself — an unwitting essay on aesthetic decline.

During table reads, I heard one of the advisers repeat, like a refrain, the doctrine of the Conventionalism of Transgressors: scandal is easy, but brings prestige. “Originality, when incessant, betrays shallow talent,” murmured a dark-coated columnist, unheard by anyone. Another adviser, with a recent book under his arm, preached that having one’s own opinion was enough — that a well-felt mistake surpassed a well-crafted form. Assistants took notes with the gravity of people deciding the climate.

In Lucio’s script there was a wedding scene: Kakía leads her daughter Calliope to the altar, where the groom Momus awaits. As witnesses stand Comus and Priapus. The rings are cast from the most common alloy of that republic: a blend of resentment, sentimentalism and scant technique. The priest — a critic without parish — invokes Shakespeare by clippings: Macbeth for ambition (without guilt), Measure for Measure for sex (without consequence).

It was tamed Shakespeare, anthology Shakespeare; stripped of the abyss that gives his words their weight.

Kalía watched the ceremony standing, arms crossed. The hall looked at her as one looks at an old aunt blocking the dance floor. Nobile tried to speak of limits that do not oppress but uphold; prudent anecdotes find no audience when the hall demands catharsis. When Speculo noticed his parents’ arrival, he transformed. The gentle young man yielded to the nervous heir, hungry for a gesture to prove his emancipation. What once resembled lightness revealed itself as fear of measure.

The film premiered. No novelty, save the novelty of offering nothing; no depth, save the certainty that the surface had been promoted to doctrine. At first, the audience laughed that light laugh which protects against second-hand embarrassment. Then, following the learned protocol, it began to applaud at the right spots: the swear words (for their supposed courage), the broken taboos (for their supposed chains), the family painted as obstacle (for its supposed tyranny).

With each applause, the large mirror at the back expanded the audience’s reflection until it slowly occupied the entire screen. It was the perfect pedagogy of aesthetic decline: choreographed indignations, handbook courage, and the comfort of never risking a form.

The jury gathered. On the table lay a coin bearing the effigy of Gresham — not the economist, but the laic saint of cultural committees: “the bad drives out the good”, read the inscription in vernacular Latin. Voting consisted of tossing the coin into the tray of wounded sensibilities. Lucio’s film had no memorable scenes, but accumulated symptoms; and where causes demand effort, symptoms earn laurels.

Each council member had the right to twelve votes. One proudly told everyone his method was simple and direct: he first voted for his friends, then asked his two lovely children to choose the remaining candidates. Thus he arrived with his conscience well resolved. Besides this singular system, he cultivated manias; he liked to translate names into numbers, as if the letters of old Latin concealed some hidden truth.

He kept these ciphers in notebooks no one read.

Someone, perhaps out of zeal, recalled that tradition recognizes merit in meticulous work: focus, framing, lighting, breathing. Then a counselor explained, with catechismal patience, that there were two orders of greatness: that of Technique, which anyone can learn; and that of Authenticity, which is born ready. What used to be called ineptitude was rebaptized sincerity. And sincerity, they all agreed, is an argument that admits no reply.

The Oracle of Astonishment was granted at last to Lucio Speculo — less for the film itself than for the symbolic narrative it proclaimed: a son freeing himself from oppressive parents. The Reed in the Wind was also awarded to him, as a golden witness of his lightness and his bold approach to social inequality.

The president quoted, from unreliable memory, a philosopher who once warned us to think well; but he swapped verb and purpose: “Let us strive, therefore, to feel intensely. This is the essence of morality.” The audience rose, not for the philosopher but for the mirror. The Academy no longer distinguished between work and crowd.

As I left, I saw Kalía and Nobile in the lobby. She with the offended gaze of forms disregarded; he with the discreet sadness of a man who knows that once proverbial bridges are burned, they demand whole rivers to rebuild. “There are still lines,” she said, as one states an axiom. “And lines preserve people.” No one heard. Nearby, a reporter collected testimonies about the film’s “redeeming courage”.

That night, in my storeroom of cloths and powders, I measured an abandoned mirror. On its back, someone had written a gloss: “Vulgarity is democratic; delicacy, aristocratic. When democracy takes offense at delicacy, it condemns itself to perpetual coarseness.” I do not know if it was a quotation; it sounded old. Above it, a note: “Do not confuse compassion with the exhibitionism of pain.” I thought of certain recent books and suspected familiar authors, but at the Academy it is prudent not to name names.

Speculo passed me in the corridor days later. He greeted me with a brief nod, as one nods at a mirror no longer needed. He seemed relieved. That week, invitations fought over him. To the reporters, he recited the liturgy: spoke of the need to strip away restrictions and of moral boldness — words the assembly loves for sparing it of content. A columnist, devout of trends, proclaimed Speculo a liberator. Of what, no one could say, which is always best: vagueness bestows greatness.

There were, as in every cult, discreet dissidents. An old professor — one of those who still read plays as work — observed that in Shakespeare evil appears without excuses; it is evil and that suffices, demanding resistance and punishment, not awards and speeches. They shrugged. The Academy is not offended by evil; it is offended by judgment.

What followed was slow and visible only to a few. Kalía left the city one morning with a light suitcase. From afar, I watched her silhouette crossing the square. No statistics recorded it, but the light changed. Shadows, once sculptural, sprawled.

Nobile left the next day, without luggage, as one who knows nothing belongs to him. His departure stirred no emotion; all emotion was reserved for the next announcement of offense.

Without his parents, Speculo grew confident. Transgression grows poor when no one opposes it; what once had the furtive pleasure of challenge hardened into mere habit. Critics — always generous once the risk has passed — named this new emptiness style. Young people, denied a language while given a megaphone, became severe wardens of compulsory lightness. The mirrors, polished by hands like mine, ceased to reflect anything but the audience.

Then they fired me. “Your surfaces are too transparent,” they said. “A good mirror must veil; truth offends.” Before leaving, I asked the doorman to let me spin, one last time, the spherical mirror that functioned as a kind of plaque at the entrance. On the visible side, one could read the house motto, which the president had quoted when delivering the prize: “Let us strive, therefore, to feel intensely. This is the essence of morality.” I turned the sphere.

On the opposite point, in homely Latin, was the original phrase: “Let us strive, therefore, to think well. This is the principle of morality.” While I read it, the doorman dutifully rotated the sphere back to the proper side.

I left. I never again saw Kalía or Nobile. At times I think of them on mornings when the light falls straight and humble upon things, and in them reappears, once more, the possibility of form. Speculo continues his award-winning career: each year a new jury decides he has surpassed himself in audacity, and the audience, duly trained, is moved. Watching is no longer necessary; the news suffices.

At night, at home, I keep a single frameless mirror. I do not polish it: I let the dust provide, from time to time, an index of our honesty. When I look at myself, I am tempted to applaud and abstain. Some taboos, I learned too late, protect us from ourselves. And when I wonder whether Speculo was a film, a man, a symbol, or a trick of names, I recall what I learned in that house: to grave matters we now give cheap words; to what is cheap, we grant solemn laurels.

If one day Kalía and Nobile return, perhaps they will bring with them a small patience and a small severity; nothing heroic, nothing theatrical. Perhaps they will set tables back in place, measure lines again, restore to courtesy its old splendor as shield. Or perhaps not; perhaps it is too late and time prefers spectacles. In any case, evil thrives when boundaries fall; art grows poor when it mistakes resentment for depth; and we, who love mirrors so much, will one day have to look out the window.

Between automatic applause and the memory of lines, we are left to choose whether we accept aesthetic decline as destiny, or return to measuring things.

Meanwhile, the prize goes on, applauded without anyone knowing exactly why. The city, absent from all maps, learns to confuse shouting with music, shock with courage, sincerity with form. Gresham’s coin — painted on the Academy wall — keeps falling on the same side. And Speculo, who was once a pleasant young man, now greets his technicians in passing; they have learned to smile without showing their teeth.

They say that one night, after yet another ceremony, an old man — no one knows if critic, poet, or simply someone still capable of blushing — dared an inconvenient question: “And what if the greater boldness were, once again, measure?” There was no answer. Automatic applause rushed to fill the void, and the mirror of the hall, out of politeness, erased the question from its glass. Then the session was closed — a session, like all sessions there, designed never truly to end.

One last doubt assails me: can we, with impunity, remove a brick — even a single one — from a foundation?

Porto Velho, March 2nd, 2025

M. – Liber Sum

Tips for attentive readers:

- The awards, echoes of other awards.

- There is a Pascalian sphere hidden among the mirrors.

- The characters’ names say more than they seem.

- The date of the story may not be just a date.

See also the author’s short stories:

For further perspectives on aesthetic decline, visit:

For a contemporary non-fiction reflection on the aesthetic decline of cinema, see “The Dying Nature of Cinema” (Treble Hook, Mount Marty University):

Comments

You may send comments on this short story using your real name or a pseudonym.

Your email address will not be displayed publicly.

To preserve the atmosphere of Liber Sum, all comments are read and approved by M. – Liber Sum before being published.